Monday, January 16, 2012 12:00 PM

Most religious structures built over the last two centuries were designed to accommodate the traditional threefold aspects of congregational life: worship God, educate the members, and build community among the faithful. Certainly in some instances, provisions were made to support social outreach, but these basic programs were the functional parameters by which faith communities understood their reason for being and gave shape to the buildings they created.

Most religious structures built over the last two centuries were designed to accommodate the traditional threefold aspects of congregational life: worship God, educate the members, and build community among the faithful. Certainly in some instances, provisions were made to support social outreach, but these basic programs were the functional parameters by which faith communities understood their reason for being and gave shape to the buildings they created.

However in the present day, as many congregations face the harsh realities of declining membership, shrinking budgets and deteriorating buildings, it is time to look beyond the traditional parameters that defined congregational life and explore alternatives. Religious leaders need to take greater initiative in creating innovative ways in which to use its real property for unconventional ministries before congregations are forced to close. An example of such creative leadership exists in the Episcopal Diocese of Washington (D.C.).

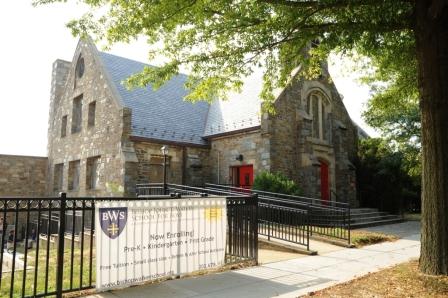

The Church of the Holy Communion is an Episcopal congregation that has served the historic Congress Heights neighborhood in Southeast Washington, DC since 1895. For the first half of the twentieth century, Congress Heights was an integrated, working-class neighborhood, populated to a large extent by whites. As demographics and economic opportunities shifted following World War II, the profile of the neighborhood gradually changed to become primarily African-American and low income. Holy Communion, which had a congregation of as many as 800 members during the 1960s, experienced decline as members moved out of the neighborhood, grew older and died. Over the same period, the effort made by the congregation to reach out to those who now live in the neighborhood and invite them to church did not produce sufficient new members to offset the decline. As a result, Holy Communion reached a point where it averaged fifteen to twenty people at Sunday worship and only could afford a part-time clergy person. The existing Gothic-Revival church and educational wing were constructed in 1952 and 1957 respectively, when the size of the congregation was at its height. Not surprisingly, as the congregation shrank, the buildings suffered from deferred maintenance. In other words, by 2005, Holy Communion teetered on the verge of closure.

At this same time, the Episcopal Diocese of Washington was taking decisive action to address another issue—the critical academic and social needs of young boys from low-income families in the District of Columbia. The Diocese committed itself to establishing a boys’ school, honoring the memory of Bishop John T. Walker, the first African American Bishop of the Diocese, and locating the school in the economically-challenged Southeast quadrant of the city, where the need is great. Yet with limited financial resources in hand, the prospect of purchasing land and building a new or buying an existing structure and renovating it seemed beyond the reach of the Diocese.

Recognizing the instance of two struggling ministries—one diminishing and the other fledgling, Diocesan leadership devised a creative solution: establish a partnership between Holy Communion and the Bishop Walker School, whereby the congregation provides the real property on which both ministries can function, while the School provides the resources to renovate the church and educational wing to accommodate both programs. The congregation will enjoy the benefit of a newly-restored facility on the weekends, while the School will bring new purpose and vitality to the property during the weekdays. Each ministry will enjoy the benefit from partnering with the other.

Both entities were agreeable to the partnership. So working with Devrouax & Purnell Architects of Washington, Holy Communion, the Bishop Walker School and the Diocese together created a design to rehabilitate the existing buildings to accommodate the first phase of the School’s growth—from Junior Kindergarten to fourth grade, to upgrade the facilities to meet current building codes and provide accessibility for the disabled, as well as to preserve the congregation’s worship space all on a frugal budget of $2.3M. In the fall of 2010, the congregation resumed worship in its historic church, as the School moved into its new spaces of the shared facility.

Is the partnership proving to be a success? By and large, it is. Still, challenges often occur in the early stages of any relationship. The most notable glitch is that Holy Communion’s congregation is yet to enjoy an appreciable increase in members and giving. The expectation was that the partnership, with its revitalization, inherently would attract new members to the congregation. Yet, reality is proving that Holy Communion still must undertake the hard work of reaching out to people in the broader community and providing them a spiritual home.

Nevertheless, this creative partnership deserves attention, applause and encouragement. Not only was a faith community saved from closing, but a vital new ministry established. The visual presence and tangible efforts of a religious institution were enhanced and extended in a neighborhood needing positive influence and assistance. Revitalizing the buildings and grounds brought money and jobs into the local economy, as the larger city benefits from preserving the historic streetscape. In short, this partnership helped a great many people who needed it.

And what is more, this model of partnership can be replicated. Examples where congregations partner with assisted living facilities for the elderly and disabled or with secular community centers to meet the needs of the surrounding neighborhood exist and are successful. At the heart of each success are creative religious leaders who recognize the needs facing their faith communities, as well as their secular communities. By matching needs with programs, real property improvement with philanthropy, and utilizing the skills and experience of design professionals, along with a dash of entrepreneurial spirit, these leaders are crucial in developing successful, adaptive-reuse solutions that address the challenges of declining congregations before their demise.