Back in the mid-1990’s, I left my practice of architecture and set off for seminary in Sewanee, TN. My first day there, I was met by this bespectacled, gray-haired man who mumbled something that sounded vaguely like an introduction and then he directed me to follow him to his office. This gentleman was Marion Hatchett, of blessed memory, longtime Professor of Liturgics and one of the people instrumental in giving shape to the 1979 Book of Common Prayer. When we arrived at his office, Professor Hatchett said to me, “Since you’re an architect, you need to know this. Read, mark, learn and inwardly digest it!” He then shoved this paper in my hand. It is entitled, “Architectural Implications of The Book of Common Prayer,”[1] a paper Professor Hatchett published back in 1985. From that time forward, until he died in 2009, whenever I saw Professor Hatchett, he would mention something about worship space design – either something he saw he liked or didn’t like (and it usually was the latter!). Then he wanted to know my opinion about it, with which he often disagreed and proceeded to explain why! Always the Professor!

Back in the mid-1990’s, I left my practice of architecture and set off for seminary in Sewanee, TN. My first day there, I was met by this bespectacled, gray-haired man who mumbled something that sounded vaguely like an introduction and then he directed me to follow him to his office. This gentleman was Marion Hatchett, of blessed memory, longtime Professor of Liturgics and one of the people instrumental in giving shape to the 1979 Book of Common Prayer. When we arrived at his office, Professor Hatchett said to me, “Since you’re an architect, you need to know this. Read, mark, learn and inwardly digest it!” He then shoved this paper in my hand. It is entitled, “Architectural Implications of The Book of Common Prayer,”[1] a paper Professor Hatchett published back in 1985. From that time forward, until he died in 2009, whenever I saw Professor Hatchett, he would mention something about worship space design – either something he saw he liked or didn’t like (and it usually was the latter!). Then he wanted to know my opinion about it, with which he often disagreed and proceeded to explain why! Always the Professor!

Yet, this paper (and I commend it to you) has proved to be very helpful. In it, Professor Hatchett identifies liturgical issues that are prominent in the ’79 Prayer Book and their correlation with particular architectural elements—concerns many priests rarely take time to think about. Yet if they did, they might find it would benefit immensely the churches they serve. This paper was useful for the Church at a time when it was trying to implement this new Prayer Book. And it still is useful today, as we consider the Church’s progress of incorporating these ideas over the course of the last thirty-plus years.

In his paper, Professor Hatchett states, “worship patterns [should] determine architectural settings.”[2] Let me say that again, “worship patterns [should] determine architectural settings.” This is an ecclesiastical way of saying “form follows function!”[3] Yet in the church, it often seems to be the other way around, “architectural settings determine worship patterns.” Back in 1962, John A.T. Robinson, Bishop of Woolrich, once said,

"But we are now being reminded that the church people go to has an immensely powerful psychological effect on their vision of the Church they are meant to be. The church building is a prime aid, or a prime hindrance, to the building up of the Body of Christ. And what the building says so often shouts something entirely contrary to all that we are seeking to express through the liturgy. And the building will always win—unless and until we can make it say something else." [4]

Part of the effort coming out of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer was to make our Church buildings say something else.

In his paper, Professor Hatchett highlights the following notions found in the “new” Prayer Book:

- The Holy Eucharist will be the principal service on Sundays and Holy Days.

- The Daily Office will continue as regular services, but will not be the principal Sunday service.

- Within the Holy Eucharist, the Liturgy of the Word will have its own integrity.

- The congregational nature of Baptism and Confirmation will be emphasized.

- Congregational participation will be stressed in all rites. This may include processions and physically moving about the space.

- The rites for the Reconciliation of the Penitent, the reservation of consecrated Eucharistic elements, and the use of oil for baptism and oil for the sick are available and their use is encouraged.

He then proceeds to make architectural suggestions that might accommodate these liturgical notions:

First of all, a church should have not just one liturgical center, but three:

- The place of Baptism (represented by the font),

- The place of the Word (ambo or pulpit),

- And the place of the Eucharist (altar-table).

Each liturgical center should stand out visually in the worship space, with equal dignity and visual prominence.

The font should be present at all services as a constant reminder of our baptism. It could be located near the entrance of the worship space or in front of it, but always publically positioned and not privately. The font should be large. Baptism by immersion is encouraged. Space should be provided for the Pascal Candle, a table for books, towels, baptismal candles and the chrism. Even an aumbry for the chrism could be created.

The ambo or pulpit symbolizes Christ’s presence in his Word. Ideally, one place for the Word should be provided and used for the lessons, the gradual psalm, the Gospel, and the sermon; as well as the Exsultet at the Easter Vigil. It should be a prominent piece of furniture that can hold a large Bible. Also, space should be provided around the ambo to allow torchbearers to stand near the reader. And it should be easily accessible by all.

The altar-table symbolizes Christ’s presence in the Eucharistic sacrament, and traditionally it was rather small, typically about as wide and as deep as it was high. Somewhat like a cube. It represents the altar of sacrifice as well as the table of fellowship. The argument against larger altars is that they tend to dwarf the other centers and create a physical barrier between the clergy and the people, rather than the table around which all gather. It is not necessary for the altar-table to be the center of attention, since the focus moves with the movement of the rite. But there should be only one and it should have ample space around it for people to circulate easily.

Other furnishings should be visually subordinate to the font, ambo and altar-table:

Credence table, Oblations table, Chairs for the liturgical ministers, the Paschal Candlestand, other candlesticks, the Cross, liturgical books, banners, flags, flowers, and audiovisuals.

With regard to the worship space in general:

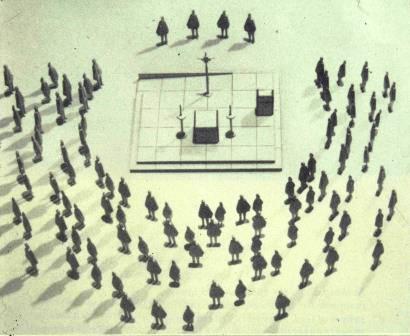

- The primary liturgical space should be shaped to encourage the relationship between clergy and laity – that all come together to form the worshiping community.

- The liturgical centers could be located on a low platform to increase visibility, but not so high as to seem like a stage – setting ministers apart from the congregation.

- The liturgical centers, along with other furnishings, could be made moveable to allow flexibility, but not spindly to suggest lack of substance.

- Congregational seating in particular should be flexible to allow for various configurations.

- Space for the choir and organ should be positioned to support the notion of the gathered congregation, while at the same time, provide sufficient musical leadership. The acoustics of the worship space also should encourage full participation of all.

- Prayer Book services demand adequate lighting levels and increasingly the ability for adjustable control.

- An entrance hall of ample size should be provided to allow for the gathering of people before and after worship, the formation of the Palm Sunday procession, the lighting of the new fire at the Easter Vigil, the formation of wedding processions, and the reception of the body at a burial. And above all, it should provide an entrance that is accessible to the disabled.

- Churches should have an adequate, working sacristy for the altar guild and a vesting sacristy for the liturgical ministers.

- A place should be provided for the reservation of the consecrated Eucharistic elements. It should be located in a sacristy or side chapel, out of the normal line of vision of the congregation, so as not to diminish the prominence of the altar-table.

- Finally, provisions should be made for the rite of the Reconciliation of the Penitent. It could be as simple as two chairs positioned so the confessor and penitent face other or a room could be created and furnished simply and austerely.

In the end, the suggestions are somewhat open, purposefully vague, encouraging to all who contemplate remodeling existing worship space or building new. The point is that each congregation must do the hard work of discernment, prayerfully considering the points of meaningful worship and how best to support it in their particular context.

So, How Has The Church Responded To This Charge Over The Past 30 Years?

Well, in my time as an ordained person with a nose for these kinds of things, I have experienced a range of responses from churches who completely reordered their worship space to those who haven’t touched a thing, and all points in between.

However in preparing for today, I thought it would be interesting to talk with a few bishops who certainly have seen a great many churches and witnessed how the larger church responded architecturally to the ’79 Prayer Book.

As a preface to all our discussions, we agreed that any change in worship space design was invariably linked to money. In other words, some congregations could afford to make changes, while other could not. Therefore, the degree of change in architecture cannot always be a direct reflection of desire.

So with this being said, all three bishops felt the centrality of the Eucharist has been widely embraced and this is reflected in the predominance of free-standing altar-tables. All believe public Baptism, by far, is the norm, rather than private, and provisions are in place to support this. However, Baptism by immersion is yet to catch on. After all, Episcopalians can only embrace so much change! The same can be said for accommodating the rite of Reconciliation of the Penitent. In most instances, two chairs are the norm rather than a dedicated space. Flexible spaces with movable furnishings are becoming more prevalent. However, accessibility for the disabled still remains a real concern.

An interesting observation beyond the influence of the Prayer Book was noted: the vast prevalence of columbaria being created in Episcopal Churches. The desire by people to be interred within the physical dimensions of their faith community is a noticeable development, and the architectural fabric to accommodate this desire has impacted most parishes.

Overall, the trend seems to be that architectural change happens as congregations can afford to make it happen. By in large, the evolution of worship space is somewhat slow. Yet for some congregations, change is an ongoing conversation. There are those who made changes early and now are considering another round. One bishop summarized the discussions nicely when he said, “We are no longer building Churches for Morning Prayer. We are building Churches for the Holy Eucharist.”

[1] Marion Hatchett, “Architectural Implications of the Book of Common Prayer,” in The Occasional Papers of the Standing Liturgical Commission: Collection Number One [New York: The Church Hymnal Corp., 1987] 57-66.

[3] “Form follows function” is an often-cited principle statement associated with modern architecture in the 20th century.

[4] John A.T. Robinson, “Preface” in Making The Building Serve The Liturgy: Studies In The Re-Ordering Of Churches, Gilbert Cope, ed. [London: Mowbray, 1962].

[Read the rest of this article...]